As well as theorising absence/silence and looking at different approaches, one thing that we want to do in this blog is look at how absence and silence become topics in themselves. Following on from The Apparent King and Queen of Silence in Politics, in this post I wanted to return to an article that caught my eye in September:

In the article, Salami asks

So why does the western feminist movement hardly look at African feminism for clues? Why does it only pay such little attention to the realisation of a once utopian fantasy of female majority leadership in Rwanda – where, since 2008, women have held over half the parliamentary seats? Feminists everywhere have spent decades campaigning for equality in political leadership, yet its achievement in Rwanda has been met with a loud silence.

There was plenty of discussion about why this might be the case in the comments below the line and it is an important question that has been posed elsewhere, but what also interested me was whether there was any way we could measure this kind of absence. That is not to devalue the salience of the perceived absence, but it constitutes an opportunity to think about methodological exploration.

Two absences are identified in the article: first, that the achievements of feminism in Rwanda have not been recognised and discussed; second that the role of African feminists in creating a more equal society have been ignored in western accounts. Any attempt to investigate these issues in a blog post is bound to be limited in scope but can perhaps indicate directions for a more thoughtful analysis and so I will look at the first absence.

One approach was to start with an open question and look at what regions or nationalities were mentioned with reference to feminism. As the article had appeared in the Guardian, I started there. The 20 geographical identities that occurred most frequently in articles which contained mentions of feminist/feminism from the last 12 months were: England, French, India, African, Western, France, Russian, European, Italy, Africa, Afghanistan, Irish, Britain’s, Egypt, States, German, Russia, Wales, Germany, Ireland. The prominent position of African and Africa challenges the assumption of silence, but of course at this stage we are missing information about how Africa is being discussed in relation to feminism: are the most frequent countries sources for inspiration or concern? To answer this we would need to go into the collocates and concordances.

Another approach that I considered was to take the two other countries that were mentioned in the article, Iceland and Australia, and as a quick test of visibility, to compare the frequency of mentions on feminist websites. The results were quite mixed, Australia tended to get more mentions that the others but the ranking of Rwanda and Iceland varied widely according to the website. With more data we would be able to get a firmer picture but the tool is still too blunt and, as above, cannot account for how the status of women is being discussed.

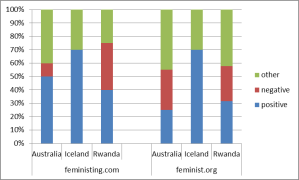

So then I looked at the first 20 mentions for each country within two of the websites and identified whether they were talking about women as victims or poor role models (classified as negative below), or if they were talking about positive role models and changes that could benefit women. This is what I found:

The situation for women in Iceland was consistently discussed in positive terms, where there was an evaluation, while positive descriptions relating to Rwanda were less frequent. The positive mentions for Rwanda related to representation in parliament; the negative mentions referred mainly to women as victims of rape, in particular during the conflict, and female genital mutilation. In the Australia data, which contained a mixture of evaluations too, the positive and negative evaluations related to similar issues: in particular advances in availability of birth control medication and legislation limiting access to abortion. This level of detail could allow for a quantitative analysis that would be a more productive avenue and also lead towards understanding western feminist attitudes to Rwanda.

Subsequent explorations which get into the discourse analysis could look more specifically at how female leaders from these three countries are represented, and in addressing the second absence identified in the original article it would be revealing to explore who is credited with female leadership success in each context.

Those interested in representations of feminism in the media might be interested in ‘On the f-word: A corpus-based analysis of the media representation of feminism in British and German press discourse, 1990–2009’